A vulture and scorpion (or perhaps freshwater crayfish, as Gheorghiu noted in his riverine ecology interpretation of 2015) among the animals carved on Gobekli Tepe pillar D43, attracted several interpretations as a ‘zodiac’. However no coherent star map, observational record, or zodiac sequence emerged. Five different identifications extensively contradict one another. The artwork is not consistent with the interpretations of Stephany (who offers two different options), Burley (supported by Hancock), Collins, or Sweatman and Tsikritsis. Yet there is some consensus that four species on other Gobekli pillars could be seasonal ‘beasts’ or cardinal constellations. As in artworks worldwide, the design on pillar D43 subconsciously expresses the five layers of archetypal structure, that we also imprint in myth, ritual, emblems, building sites, calendars, various sets of 16, 18, 24 or 36 hour decan asterisms (see the Babylonian example below), and constellations.

Characters expressing archetypes always have an axial grid between their eyes, as demonstrated below. Various zodiacs worldwide express some elements of time, symbol, ritual and myth, but cultural media expresses archetypal structure; they do not illustrate the sky. Babylo-Assyrian boundary stones, and the Mul Apin (Starry Plough) list, demonstrate that icons are apparently varied, yet structuralistically rigorous. Culture is compulsively sustained by the structure embedded in nature, in our perception, and in our subconscious behaviour; not by ‘tradition’.

Iconography offers some conscious access to the structure of perception and expression. No single artwork or cultural set contains all the variants. And no single ‘specialised’ science could interpret cultural behaviour. Inter-disciplinary study is required to reveal our subconscious connection to nature, including time and space. Simplistic correspondence theories are inadequate to the role that archaeo astronomy should play in the human sciences.

By Edmond Furter, Author of Mindprint, and of Stoneprint, and editor of Stoneprint Journal.

Comments to any article are welcome in the Comment function below.

STEPHANY SEES THE VULTURE AS PEGASUS, OR SAGITTARIUS

Timothy Stephany (2009) was among the first astronomical interpreters of Gobekli Tepe art. On pillar D43 he initially saw (clockwise from top left): bird hut as Perseus; burrowing fox as Cassiopeia; its hut as Cepheus; spider’s hut as Draco head; spider as constellation Hercules; heron as Cygnus; reed wall as galaxy; bird forepart as Lyra; rearing chick as Aquila; scorpion as Aquarius north and Capricornus tail; big bird as Piscis Austrinus; wolf as Aquarius south; snake as Pisces; dot as Lacerta; vulture as Pegasus. He did not picture the celestial equator of about BC 9500, which lay across Pegasus north; nor the three poles, which were aligned at the time. In another proposal, Stephany uses the other half of the galactic equator, and sees the bird, fox, spider and three birds as small asterisms in the galaxy, over vulture as Sagittarius, scorpion as Scorpius, and the rest in the Ara and Pavo area.

On other pillars, Stephany sees a pig as Ursa; a cup-hole above its eye as the then distantly future celestial pole at Polaris (where it is now, 9 000 or more years later), and ‘misplaced’ to Camelopardalis. But the Giraffe is 20 degrees south of Ursa Minor. And in Gobekli times the pole was at Ursa’s tail. And the rate of precession was probably slower at the time.

On pillar A2 he sees the cow as a macro asterism north of Virgo, Libra and Scorpius, its horns in Virgo at the star Spica, its back in Bootes, body in Corona and Hercules, feet in Ophiuchus. The fox he sees as Scorpius Claws, its body over the Ophiuchus feet; crane as Scorpius, its tail over the galactic centre; another fox and crane as Lynx tail over Cancer.

On another pillar he sees five rearing cranes as three stars in Cepheus, and Draco neck star Altais, and Draco’s hip, with a cup-hole as Polaris. But Polaris had no special function in the Gobekli sky. If this artwork were a ‘time capsule’, they could have used more clearly defined asterisms, or a grid.

Gobeklians probably had hour decans (see the Babylonian set below, and three kinds of Egyptian decans in Furter 2016: Stoneprint; and in an article in the anthropology journal Expression edition 13). They may have had a zodiac, probably including some of these animals, but Stephany focuses on the galaxy.

On the central pillars of the houses, Stephany sees the foxes jumping forward from the elbows of the ‘pillar people’, as a macro combination of Leo, Coma, and Virgo, with jaws at star Regulus, to tails at Spica. But Leo is never canid. Virgo may have a dog (see the Assyrian decans below), but the sky version of that canid is Lupus (see type 9c in the archetype table below).

There is no consistent scale, projection, stars, or polar context in Stephany’s scheme. He finds shreds of incidental, undeveloped, ‘un-evolved’ conscious logic. The wild goose chase for correspondences reveals popular and ‘scientific’ archaeo astronomy to be stuck in a narrow fundamentalist, developmental and diffusionist paradigm.

On dating, Stephany goes further back than any other author. On pillar D38 he sees the thin bull-fox as summer in Capricornus; pig as winter in Ursa head and Cancer; birds as autumn in Triangulum, Aries and Pleiades. Thus he implies spring and the Age in Libra-Scorpius, impossibly early.

Rampant lions in house H, Stephany sees as Gemini-Orion combinations, their bodies across the galactic gate. But no culture pictured a felid here, and it is usually a summer beast. Spring is more often two antithetical characters (as of Babylonian Nergal’s small serpopards, and the Mayan hero twins). And Stephany’s macro lion would cross the sky feet first, as reclining Gemini also does, but the ‘lion’ would face south-east, away from the horizons and oncoming planets, as precessional griffins in some emblems do.

The two donkeys on another pillar he sees as Bootes inverted, the upper front legs as Coma at the galactic pole; the second donkey as Canes Venatici (Hunting Dogs) inverted. However circumpolar constellations are rarely inverted (jumping down from the pole towards the zodiac). Stephany’s various schemes are cobbled together, like the ‘scientific’ paradigm of chance resemblances and gradual consensus. As if the Gobeklians tried hard to tell each other, and us, something about stars, and about our own time.

BURLEY AND HANCOCK SEE THE VULTURE AS SAGITTARIUS SOUTH

PD Burley (2013) interprets some Gobekli Tepe pillar D43 characters as (clockwise from mid right): half-bird and heron as Ophiuchus legs; rearing bird as Scorpius head; scorpion as Corona Australis and Pavo; dot as midwinter sun at the galactic crossing (‘in our current era’); vulture as Sagittarius south, one wing below the galactic centre.

Graham Hancock supports Burley’s interpretation in his own book, Magicians of the Gods (2015, p308 -325), and makes much of the supposed post-dating of the ‘star map’ to our current era. But why would the builders set their clock and their art forward by 90 degrees? The Gobekli autumn sun was in the Scorpius-Sagittarius galactic gate, where our midwinter sun is now (exactly so in 2016, as I published in Mindprint 2014, and noted on grahamhancock.com in an article in September 2015). Burley and Hancock leave the other characters on the pillar unnamed, and take no account of other interpretations.

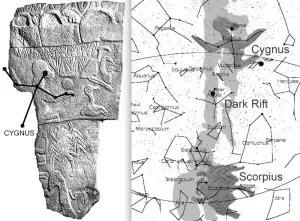

COLLINS SEES THE VULTURE AS CYGNUS, SWAN

Andrew Collins (2014) agreed with Burley and Hancock that the pillar D43 scorpion is Scorpius, but he saw the vulture as Cygnus, its head at Deneb. Both are on the galactic Dark Rift. In his scheme, the headless man (presumably at Libra?) is dying, the ball is his separated head or soul, and House D’s holed stone is rebirth. But Cygnus had no special function in Gobekli times. Collins sees many monuments worldwide as aligned to Cygnus rising or setting, including Avebury (but see a more coherent analysis in Stoneprint p254-255), and the Giza pyramids (but see a more coherent analysis in Stoneprint p201-205). Collins also assumes a stable precessional rate, and a minor oscillation in obliquity, after the Stockwell and Newcombe curve. But Dodwell (2010, see below) contradicts stable obliquity based on known historic obliquity data.

SWEATMAN & TSIKRITSIS SEE THE VULTURE AS SAGITTARIUS NORTH

Martin Sweatman and D Tsikritsis (2017) interpret the Gobekli Tepe pillar D43 artwork as a kind of calendar (clockwise from top left): Bird as Pisces. Fox “ibex” (but without horns) as Gemini. Spider “inverted frog” as Virgo (but two similar spiders on pillar D33’s edge do not resemble frogs). The four ‘bags’ they see as four seasons (but not spaced by their places in the supposed ‘zodiac’). Reeds as abacus for counting dates, planets or comets (but the pillar does not have apparent numerals). Flamingo and ibis as Ophiuchus. H/I-shapes as former pole stars Vega and Deneb (but they are at the edge, thus south of the Ophiuchus. Identical abstracts appear in rock art worldwide). Sitting bird as Scorpius claws or ‘an obsolete asterism’. Skin “man” as death hieroglyph (but why not also a constellation?). Scorpion as Scorpius reversed, head in tail, tail in head (but its universal feature is a tail south-east, bent north-east). Big bird as Libra. Wolf as Lupus (but the asterism does not resemble any animal, thus other factors keep a canid here. See the Assyrian list below). Snake as comet or meteor shower (but showers radiate from specific points. And why not also a constellation?). Circle as midsummer sun (but why in the polar area?). Vulture as Sagittarius (but why reversed, tail first?).

They place Gemini opposite Scorpius, implying a celestial, observational grid, with a celestial pole more or less over Libra. But their four Age Gemini cardinals are on top, thus a kind of calendar and not a zodiac. They explain the positioning as “constrained by the shape of the pillar.” But the design compares to any inspired artwork worldwide (see the archetypal analysis below), and no features seem to be crammed in.

Sweatman challenges archaeo astronomers: “How many configurations of Pillar 43… are a better fit than the current one?” But several are, judging by at least five others, and by the various options that Sweatman keeps open, including “perhaps meaningless”. They claim to have found “orientational ordering of animal symbols” around the scorpion. But no clear scheme emerges. To this shaky edifice they apply several doubtful dating methods (see the dating section below).

DIFFERENT ‘ZODIACS’ MEAN NO ZODIAC

No single ‘zodiac’ interpretation of Gobekli pillar D43 makes astronomical, iconographic, mythic, ritual, theoretical, precessional, or archetypal sense. Each different ‘astronomical’ interpretation adds evidence that the art is not astronomical. Stephany’s two proposals (labelled A or B in the tables) also differ.

Table 1. Four ‘zodiac identifications’ of pillar D43 compared, clockwise from top left.

| ENGRAVING | Martin Sweatman | Paul

Burley |

Timothy

StephanyA |

Andrew

Collins |

| SmallBird | Pisces | ? | ? | [Pegas.?] |

| FoxBurrower | Gemini | ? | Cas.Ceph | [Lacerta?] |

| Hut bag | [Cancer?] | ? | Perseus | ? |

| Hut bag | [Leo?] | ? | Draco | ? |

| Spider | Virgo | ? | Hercules | ? |

| Flamingo | Opihuchus | Ophiuchus | Cygnus | ? |

| Ibis bird | Ophiuchus | Serpens | Lyra | [Herc.?] |

| Bird-snake | ? | ? | ? | [Draco?] |

| Bird squat | Sc.Claw | Scorpius | Aquila | [Oph.?] |

| Bird tailcoat | Sc.Claw | Scorpius | ? | [Oph.?] |

| Skin bag/man | (death) | TriangA | ? | (death) |

| Big bird | Libra | PavoBird | PiscAus | [Libra?] |

| Scorpion | ScorpRev. | CoronaA | AquarN | ScorpRev. |

| Wolf | Lupus | Telescop. | AquarS | ? |

| Serpent | (comet?) | SagitrSouth | Pisces | [Ara?] |

| Circle | Sun | Sun | Lacerta | (soul) |

| Vulture | Sagittarius | Sagittarius | Pegasus | Cygnus |

Table 2. Potential agreements between ‘zodiac identifications’.

| ENGRAVING | Sweatman | Burley | StephanyB | Collins |

| Flamingo | Opihuchus | Ophiuchus | Ophiuchus | |

| Bird squat | Sc.Claw | Scorpius | ||

| Scorpion | ScorpRev. | Scorpius | ScorpRev. | |

| Vulture | Sagittarius | Sagittarius | Sagittarius |

The only general agreements on this pillar are the vulture as Sagittarius, scorpion as Scorpius, and the flamingo as part of Ophiuchus; but these asterisms are seen in different orientations and contexts, even reversed. Prof Vachagan Vahradyan of the Russian-Armenian or Slavonic University, and Juan Belmonte, also see the scorpion as Scorpius, but probably in the current Western configuration. These three flawed agreements, against about fourteen disagreements, raises suspicion of prejudice, and some coincidence. If there were a horse, would that be Sagittarius? Or Pegasus? Every bull is not Taurus, every fish is not Pisces, every twin is not Gemini. Correspondence ‘theory’ merely elaborates some common sense assumptions about culture. Could archaeo astronomy tell the difference between a myth cycle, a calendar, a zodiac, emblems, divination sets, and a star map? Could it reveal the core content of culture, or explain perception? Correspondences simply mix and match shapes and star lore. Archaeo astronomy needs better theories, and a more scientific paradigm, to rise above the level of a parlour game. Even crafts such as astrology are way ahead of the trans-disciplinary science. And the human sciences do not study crafts such as ritual, myth, emblems, astrology and divination at all, thus removing half of human behaviour from the scope of the humanities.

There is a deeper common source of cultural meaning. There is “something more mysterious going on”, as Graham Hancock wrote in his warning against using Zecharia Sitchen’s science fiction or ‘space archaeology’ novels as ‘research data’. The entire conscious, fundamentalist, common sense paradigm of archaeo astronomy is wrong. The “mysterious” thing in the cultural record, is that we have a large universal repertoire of standard subconscious behaviour. That behaviour is imprinted all over the cultural record. But our conscious mind finds it hard to see what is hidden in plain sight. The consequences for our self-image are significant. We did not invent, develop, or change culture. Culture is part of the human package, at least since Gobekli at BC 8000, cave art about BC 20 000, Blombos shelter about BC 70 000, and perhaps even Border Cave about BC 100 000, with the usual ensemble of tools, clothing, cosmetics, and trade. Human behaviour is static, and thus predictable, down to the structure of artworks and building sites.

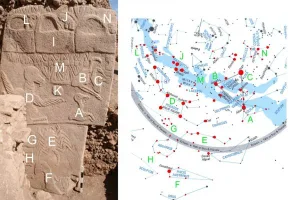

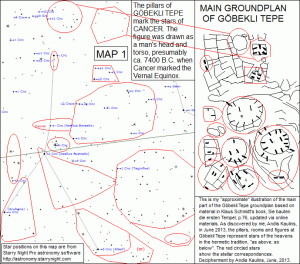

GOBEKLI HILL: KAULINS SEES CANCER, HERSCHEL SEES PLEIADES

Andis Kaulins (2013) extends his view of various sites as star maps, to Gobekli hill as Cancer. But where is the Hydra head? Why are there two lion houses at the supposed Lynx tail? Why would Younger Dryas people model a village on a dark zodiac constellation? Kaulins believes an ancient survey committee travelled the world to imprint constellations by way of cup marks and enhancing incidental rock profiles; an archaeo astronomy conspiracy theory.

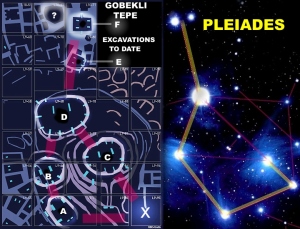

Wayne Herschel (2013) extends his obsession with the Pleiades, and a supposedly habitable planet near its thin end, to Gobekli hill. The archaeo astronomy popular fringe likes codes, maps, time capsules and ‘alien origins’, as Hollywood movies oblige. But many of the sites where Herschel imagines Pleiades maps, express the full repertoire of subconscious structure, unknown to the builders (Furter 2016: including Far Eastern, European and Mayan sites). Pleiades is part of type 2 Builder, which expresses just one of the sixteen types, always at a smaller scale than Herschel’s mega cluster proposals, and not deriving from the sky. ‘Cluster’ is one of the recurrent features of type 2 Builder, and the sky happens to have a cluster in the appropriate place. But not all constellations happen to express archetypal features in the appropriate place. And Pleiades did not mark any seasonal point in Gobekli times. The cluster rose to mythical and ritual prominence from about BC 2300, when it hosted the spring equinox, and remained prominent through Age Aries, up to about BC 80, since it is nearly on the ecliptic, and cardinal (90 degrees) from Leo Regulus, Scorpius Antares, and Aquarius decan Piscis Austrinus.

Popular assumptions in archaeo astronomy are more consistent than their supposed evidence is. Herschel, like many archaeo astronomy and science fiction authors, impose populist myths on the cultural record, and impose various conscious motives on artists and builders, particularly lesser known cultures. Real mythographers and artists express a deeper and more consistent level of archetype. Popular science deals in shallow, rationalised and politicised myth. Even the doyens of ethno astronomy, De Santillana and Von Deschend (1969), fell victim to the ‘scientific’ common sense paradigm of culture. Did Icelandic myth cycles arise from astronomy, degraded to legend? Or do myth, ritual, art and calendars express a common source of culture, each directly from archetype, with occasional references to one another? These cross-references are easily mistaken as deriving from one another, and thus they camouflage their source.

CIRCULAR DATING AND PRECESSIONAL ASSUMPTIONS

Sweatman and Tsikritsis make elaborate arguments and extravagant claims for dating Gobekli artworks: “The probability that pillar 43 does not represent the date 10 950 BC is around one in 100 million.” This date happens to agree with the probable Younger Dryas event, but not due to their methods. Some Gobekli wall plaster was dated to BC 9530 (Dietrich & Schmidt, 2010), a thousand years after the probable impact. Some Gobekli researchers have noted that the soil infill and carbon and bone items in the plaster was older than the buildings, which may date to BC 6000s. Sweatman sees no obstacle in a thousand years, and proposes a local observational record going back to BC 16 000, about 4000 years before the earliest possible dates for any human presence at Gobekli. They use a syllogism to test their proposed ‘meteor observation records’ and “find an apparent contradiction of our first proposal; resolved when we apply the second proposal. Logically, this implies significantly improved confidence in both proposals.” Thus their ‘zodiac’ identifications, and dating based on assumed observations and certain meteors, and the geological record, all have to agree for their proposal to work (Their title of ‘What does the fox say’, is parodied in an archaeology blog; ‘What does the bunny say’). They place midsummer in Sagittarius in BC 10 950, or rather between Sagittarius and Scorpius, judging by their graphics. But astronomy automation uses modern values for the rate of precession, which is known from Nasa data to be slightly speeding up, and may have been much slower in the distant past.

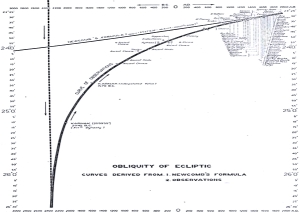

Astronomy automation programmes assume a narrow oscillation of obliquity after Stockwell, as adopted by Newcombe. But Egyptian, Chinese, Hindu, Greek, Arabic, Medieval, historic and Mayan data contradict the ‘Newcombe’ curve. Obliquity had reduced at a slowing rate, indicating a larger bump, and fast initial righting; and a semi-oscillation of 599 years (Dodwell 2010, in Setterfield). In the Dodwell graph, the curve should be wavy due to the semi-oscillation that he had found. In addition to these astronomical uncertainties, in an era 5000 years before the earliest and rarest Babylonian and Egyptian astronomical data, earth’s orbital diameter may have been larger, and the moon’s orbit larger; and time slower. There was a different equation of time, or Delta-T, in geological time (Williams et al 1998), which may have extended into the Ice Age. Thus automation errors grow exponentially larger further back. But Sweatman and Tsikritsis “know of no reason to question Stellarium”.

Using equinox and solstice sunrise and sunset as calibration dates, and their software, they see a Gobekli midsummer horizon sun at BC 10 950, and a spring horizon in BC 18 000. But the pictures on pillar D43 do not apparently mark a star map horizon. All the characters are more or less upright. Zodiacs tend to picture animals facing ecliptic west. Seasons remain in the same constellations for about 2000 years, depending on how constellations are defined.

The H/I shapes at Gobekli, Sweatman sees as “former pole stars, slightly north of Serpens”, at Vega BC 11 500 and Deneb BC 16 000, “still referenced [in the Gobekli era]… to define north or a preferred direction, by the general orientation of enclosure D, 5 to 10 degrees west of north… at summer solstice sunset… at an altitude of 42 and 67 degrees.” But this is too high up, and too long before Gobeki, to have served as a meridian; while contradicting their daily and nightly visible north. And it implies two thousand years of stubborn conservatism at Gobekli. Or, if it is all “mostly abstract”, as they say, it is not astronomy. And if it is outdated by 2000 years, then it is not astrology, which works on the celestial grid, and from the moving spring point. And ancient religions probably did not last 2000 years. Sweatman adds rhetoric of a supposed Deneb in Lascaux caves (Rappengluck 2004); and of a southern view to Sirius rising (Magli 2016); near the winter sunrise and sunset (Gonzalez-Garcia 2016); and of the Taurid meteors in winter. Then they dismiss orientations as immaterial to their zodiac picture! Their rhetorical wild geese fly all over the sky, but keep their options open by remaining on the ground.

Sweatman and Tsikritsis count thirteen characters on pillar D43, but they exclude the skin bag “man”. Lunar calendars do have thirteen months (at least in recent, known epochs), but the moon does not seem prominent in Gobekli art. And the odd number runs counter to astrological geometry. ‘Thirteenth sign’ theories mistake Ophiuchus and Scorpius, one of the four doubled constellations, as two “signs”, without separating the other three doubles (Taurus Orion, Leo retro, Aquarius Pegasus legs).

Figure 8. Gobekli Tepe pillar D38: bull-fox-bear with horns down, over pig, over three cranes. They could express seasons. Is the griffin on top Capricornus or Virgo? Or are they Ursa with the celestial pole, Sagittarius, and Pisces? The apparent dent in the griffin’s lower muzzle is a cup-mark, or ancient damage.

SOME CONCENSUS ON SEASONAL BEASTS

The four houses or “bags” at the top of pillar D43 are equinoxes and solstices sunrises and sunsets in Sweatman and Tsikritsis’ view, thus four seasons. These they see as Pisces, Gemini, Virgo, and Ophiuchus below right of the others, apparently a celestial grid deviation from their Scorpius. But why is the pelican house not their Sagittarius? And their proposed pole over Scorpius should change their Virgo to their Libra. Astrological beasts and ‘houses’ are used in all cultures, but Sweatman says nothing about astrology, or about iconography itself. Should scientists study ancient ‘science’, and not ancient crafts?

Astrologers practice a broad spectrum of archetypal applications, and they outnumber archaeo astronomers by thousands to one. Yet none have volunteered an astrological interpretation of pillar D43, probably since it is not a practical zodiac.

The search for four seasonal beasts could reveal the astrological Age of the artists. Pictures of four species on two other Gobekli pillars may be the seasons. But to Sweatman and Tsikritsis they chart the changing position of the two Taurid meteor showers during observation of 10 000 years!

Pillar A2 stacks images of a cow, fox, crane. Pillar D38 stacks a bull/fox/bear, pig, three cranes. These Sweatman sees as Capricornus, Aquarius north /south, Pisces; wherein the Northern and Southern Taurids may have progressed (moved forward against background stars) during Gobekli civilisation. But a fox in Aquarius is doubtful. And there is no sign of meteorite radials or snakes in their ‘Pisces’ area, the top left house, or anywhere else. After Gobekli, the Taurid streams may have moved on from Pisces, via Aries and Cetus, to Taurus, if precession was regular, and if these meteorite orbital nodes did progress at six degrees per 1000 years (citing Asher and Clube 1998). From all of this, Sweatman and Tsikritsis “estimate the probability” that their interpretation is coincidental, at 2%, or 98% certainty. But the sky has about twelve regions that could fit these four species, either along the ecliptic or on meridians. And which of the four hosted spring? That alone makes a difference of 6000 years (or more, if precession was slower). Archaeo astronomers are lavish with time. The Ursas could picture any of these four species, and still do in some cultures, partly since Ursa is near the poles, and spans 70 degrees; and Ursa Minor overlaps 30 of these degrees, and adds another 20 degrees. Together they span 90 degrees, covering the ecliptic grid over Leo, Cancer and Gemini, a quarter of the annual sky. There are potential bovids in Taurus, Capricornus, Virgo, and the Ursas (bull legs in Egypt). And potential foxes in Aries, Gemini, Libra, Perseus, Lynx, Bootes, Ursas, and the celestial pole. And potential pigs in Auriga, Cetus tail, Cetus, Canis Minor, Sagittarius, Aquarius, Hydra neck, and Ursa. And potential cranes in Gemini, Pisces, Cancer, Hydra, Ophiuchus, Lacerta, Draco, and Ursa Minor. These options, including Sweatman and Tsikritsis’ candidates, reduce their pseudo-statistics from “98%” to about 8%; provided that pillars A2 and D38 picture two V-shaped legs of observations of the Taurids’ real motion over 10 000 years! No culture has astronomical records that long. Constellation variants do not remain in use that long. Seasonal beasts are updated every 2000 years. And the two ‘beasts’ pillars are far apart. They deserve ridicule for their dating construct, but credit for continuing the search for the four seasonal beasts, which Stephany had started.

The pillar A2 cow seems pregnant, inviting structuralist analysis (Furter 2017, in the anthropology journal Expression; Pregnant is the most consistent typological gender. Citing massive rock art gender data on the rarity of female characters in rock art, of Laue 2015, ASAPA conference paper, in press). A womb is nearly always type 11, also expressed in Virgo constellation and her alpha star, Spica. The sun in her horns offers the best iconographic date at Gobekli Tepe, since it probably expresses, and perhaps consciously pictures, midsummer sun and celestial pole. All three poles were aligned on this ecliptic meridian in Age Gemini-Taurus (the seasons are always 90 degrees apart). If Gobeklians knew any astronomy, and if the daily celestial pole lay between the invisible galactic pole and the annual orbital pole, we could know where the four seasonal points were. The A2 pregnant cow seems to picture Bootes, who stands over Virgo, and held the celestial pole in his ‘horns’ before this axial era. A2 is a central pillar, supporting the polar interpretation.

The A2 cow’s counterpart on pillar D38 (see the image) is a thin bull-fox or lion-bear. If Gobeklians placed this griffin in the sky as well, it may have been Ursa retro, with the celestial pole in its ‘horns’ at the time (some art traditions picture constellations retro, in the context of precession, usually monsters, not the familiar figures turned backward). Bootes and Ursa held the pole in turn, and still did long afterwards; in Egypt as Bootes spearing the Ursa bull foreleg (Bauval 2006), then spearing the Draco tail, then spearing the Ursa Minor smaller foreleg or Wippet ‘mouth opener’.

Pillar D38 expresses type 4 Pisces in house D, thus the Gobekli winter (Furter 2016; Stoneprint). Subconscious expressions never fully coincide with craft applications such as myths, rituals, art, and zodiacs, but since we do not have direct access to any of their conscious or rationalised media, we have to read the iconography, and compare potentially conscious elements in its symbolism to other early artworks, particularly Ice Age and Sumerian textual legacies (see the Plough list below). If these four species were seasonal beasts, they fit Age Gemini well: A2’s cow as Virgo, fox as Gemini, crane as Pisces; D38’s griffin as Ursa, pig as Sagittarius, three cranes as Pisces (which is two birds in the Persian zodiac, and three birds or fish in the archetypal myth map I had published in Mindprint, and in Stoneprint).

Table 3. Four Gobekli species as seasonal beasts in Age Gemini-Taurus.

| D43 | A1; D38 | FEATURES | CONSTELLATION | SEASON |

| Egg | Cow, sun;

Griffin, sun |

womb, polar

bear?, polar |

Virgo, Gal. Pole

Ursa, Cel. Pole |

summer |

| Fox | Fox | canid | Gemini, gate | spring |

| Ibis | Crane/s | birds, twins | Pisces, solstice | winter |

| skinbag | Pig | skinbag | Sagittarius, gal.centre | autumn |

These four animals swop positions in art, like medieval cardinal beasts in pillar decoration also do. On pillar D43, each has some features of Age Gemini and Age Taurus1, typical of transitional Age artworks. Fox burrows down over the Gemini-Taurus gate; vulture expresses Virgo and the two Leo types in the same body; skin bag rides on the Scorpius big bird’s back; ibis has the tailcoat body of type Aquarius. In iconography, the subconscious structure remains remarkably consistent, and out of conscious reach, unless systematically demonstrated. Only archetype could sustain this hologram, and its expression in various media, and its craft applications, such as astrology. Crafts do not sustain one another. Thus myth, art, ritual and architecture have their own inspiration and conscious rationalisations, including occasional illustrations, or rather references to one another. These references lure common sense, and science, into the traps of apparent diffusion. The five layers of subconscious structure, and their known elements (see the table below), is over the heads of artists, yet they all express it fluently. Like grammar, iconography is an innate, subconscious competence. Viewers also do not know how it works at deeper levels, but could instantly tell if it were absent.

In myth, fox is the trickster, as Sweatman points out. The entertaining villain may have been a pet, exterminator of vermin, hunting aid, pelt source, perhaps food at Gobekli, where many fox bones were found (Schmidt 2013). There were no dogs yet. Ethiopian, Egyptian and alchemical art makes much of red foxes.

‘ACCURATE SPECIALISED OBSERVATORY’?

Gobekli Tepe hill was “also an observatory”, propose Sweatman and Tsikritsis. But the wet climate, and annual runoffs of mud melt in the Younger Dryas, and animals such as hippo, probably necessitated mountain sites to survive, and hilltop sites (preferably facing south to the sun) to move to the slowly drying plain. Even Arabia was swampy until historic times, and Giza was an island (Gigal 2016).

They propose that “people of Gobekli Tepe were making accurate measurements of precession.” But how could we tell? There is no clear record in the art or in the buildings (but see the subconscious polar precessional tracks in house C, in Stoneprint). Their motivation? “To communicate to potentially sceptical generations… that a great truth about the ordering of the world was known… important for continued prosperity and perhaps survival.” This is science fiction, not archaeo astronomy or archaeometry. “Given the considerable lead-time in developing this knowledge,” (what knowledge? that earth crosses meteor paths all year long?), “we should not rule out even earlier demonstrations of these specialisms.” But Ice Age astronomy is rare, apart from some lunar calendars on antler bone.

Sweatman sees astronomy as the instigator of all of culture: “Symbolism encoded on D43, the date stamp… zodiac signs… H-symbols, demonstrate an early form of proto-writing… at least for astronomical observations.” Did writing develop from astronomy? Abstract shapes appear in art and rock art worldwide (Von Petzinger 2016), either badly drawn characters, or entoptics, with a surprisingly consistent repertoire (Furter 2016, Expression 13). But few known poets, artists and scientists are astronomers. If archaeo astronomy wants to contribute to the necessary interdisciplinary study of the cultural record, it needs better data, methods, terminology and theories. “Similar patterns” and “messages to the future” may be generally true, but are not scientific (Popper 1963). Sweatman’s circular logic is embarrassing: “Given the astronomical theme… the fox… should represent an asterism… to enquire whether other symbolism is also astronomical.” There is much more in the cultural record than fragments of proto-science.

CULTURE CODE IN THE BABYLONIAN PLOUGH LIST

Decanal, hourly or lunar asterisms are common in ancient art. Egypt used three different sets (Neugebauer and Parker 1969). Zodiacs of twelve characters are known from Greek times onward. The earliest known constellations are the Sumerian Mul Apin (Stars of the Plough, or Starry Furrow), of 36 or 66 asterisms. These decans added celestial authority to kudurrus (tax and contract boundary stones), often in registers that run boustrophedon (‘ox-ploughing’, rows alternating to left and right). These ‘astronomical’ artefacts express their own archetypal structure, sometimes contradicting the consciously understood asterisms, which were also subject to their own interchanges and mutations.

Table 4. Characters on the kudurru (contract stone) of Melishippak II at Susa, by archetypal number, Type and analogous Month or constellation (noting archetypal features):

2 Builder or Taurus; Enlil ram on his house (tower. More often bovid, but the former Taurus spring had newly precessed into Aries).

2c Basket or star Algol; Anu house (secret, container, woven texture).

3 Queen or Aries; Zababa raptor (long or bent neck, dragon).

4 King or Pisces; Nergal griffin (squatting) with twin post (twins).

5a Priest or Aquarius; Marduk’s house (assembly, priest).

5b Priest or Aquarius; Marduk animal (varicoloured? tailcoat?).

5c BasketTail or Piscis Austrinus; Adad’s horns (6 is often a U-shape).

6 Exile or Capricornus; Adad Storm calf (sacrifice), scalloped post (U-shape).

7 Child or Sagittarius; Shala’s house (often indistinct). The Shumalia store house (bag) bottom left could be his determinant.

7g Gal.Centre: Ninghizidda tail (path).

9 Scorpius; Shala ram (strength, more usually an ibex), with post (pillar).

9c Basket Lid or Lupus; Nushku lamp (revelation, enforcement); and plough (more typical of 3 or 3c opposite).

10 Teacher or Libra; Ninghizidda snake with forward tooth, under a staff (guard), over a scorpion claws determinant (arms up). The claw stars often interchange between types 9 and 10)

11 Womb or Virgo; Gula’s dog’s womb (womb, mother), with a granary? (wheat), fronted by a seated woman? And a vulture? (maternal) on a post (more typical of 11p).

12 Heart or Leo; Heart (heart) of Ninurta lion (felid).

13 Heart or Leo; Ninurta lion (felid, death, war).

14 Mixer or Cancer; Ninhursag’s house with wedge (polar).

15 Maker or Gemini; Ea goat-fish (more typical of 6), leg out (rampant). Type 15 should not be a goat-fish, unless the Age Taurus-Aries midwinter transition in Aquarius-Capricornus is transferred to the top central position.

Axial centre; Unmarked as usual.

4p Gal.S.Pole; Paw (limb joint).

11p Gal.Pole: Granary guard’s hip? (limb joint).

Midsummer; Horse post’s foot (limb joint), between axes 13 or Leo and 14 or Cancer; implying spring and the cultural time-frame in Age Taurus-Aries; confirmed by type 15 or Gemini at the top centre of the spatial structure.

All five layers of structuralist expression are subconscious to artists, architects, builders and members of any culture. Babylonian asterisms are assumed, based on late Egyptian and modern reconstructions of the Greek zodiac. In Sumerian myth, decans were arrayed on three latitudes or equators: north Enlil 33 (galactic?), central Anu 23 (ecliptic?), south Ea fifteen (celestial?); or a heliacal 34, or a lunar 36. The Enlil 33 is best known from the Assyrian Plough list in seasonal sequence, probably hour markers (adjusted every few weeks), listed here by likely archetype numbers for comparison to artefacts worldwide (with globally recurrent features in brackets).

Table 5. Assyrian copy of Babylonian ‘Plough Furrow‘ hour decans, in seasonal sequence (opposite to the hour sequence), by archetypal Number, Generic label; analogous Asterism; and Babylonian emblem (noting archetypal features):

2c Basket or star Algol; Plough; Aries Triangulum (knife), held by type 2 Perseus or type 2 Andromeda.

2 Builder or Taurus Pleiades; Large matted star (cluster, woven texture 2c). Archetypal spring ‘house’.

2 Builder or Taurus Pleiades; Seed (cluster), ploughed funnel, wolf; perhaps Hyades (cluster), or Perseus (twisted).

1 Builder or Taurus Orion; Old Man, Enmesharra; Orion or Auriga.

15g Gate or Galactic crossing; Crook staff; Orion’s club or Camelopardalis in the galaxy.

15g Gate or Galactic crossing; Large Twins (doubled, of 15), End; Gemini feet or road (gate).

15 Maker or Gemini; Small Twins (doubled); Gemini Pollux or Canis Minor.

14 Mixer or Cancer; Crayfish in estuary, Anu’s home; Cancer, Age Aries pole, archetypal summer ‘house’.

13c Head; Leo Minor (felid of 13), Latarak.

13 Heart or Leo star Regulus; King (more typical of 4, but here a warrior, typical of 13) and Lion (felid) Leg upper bone, and Ursa foreleg (death), perhaps star Duhr (Zosma).

12 Heart or Leo rear; Tail, date palm fan of Erua and Zarpanitum; star Denebola or Coma.

11p Gal.Pole; Enlil who determines Kur mountain’s ‘aptitude’ (moving limb joint angle).

11 Womb or Virgo; Zibaanna; Virgo Spica (crop) or Bootes alpha star Arcturus.

10 Galactic Pole diversion; Before Arcturus, Chegalaju, Ninlil’s messenger.

10 Teacher or Libra; After Arcturus, Baltesha, messenger of Tishpak.

10 Celestial Pole diversion; Large Wagon, Margidda, Ninlil; Ursa or slowly moving Celestial pole.

9c Lid or Lupus; Wagon Shaft. Archetypal meridian, opposite the 2c starting point. Nergal’s Fox (canid).

9 Healer or Scorpius head; Front of Wagon, Mother Sheep (opposite 3 Aries); Scorpius star Antares.

9 Ecliptic Pole diversion; Yoke (juncture on limb joint) of Anu, great heavenly one; perhaps Ecliptic pole in Draco.

9 Healer or Scorpius head; Small Wagon; Hercules (strength) perhaps an Ursa stand-in as former Age Taurus autumn marker.

9 Healer or Scorpius head; Seed Lord. Star Antares, opposite type 2 Furrow. Star on Cable; Libra scale on Serpens chain.

8 Healer or Scorpius tail; Interior of Temple (pillar), first son of Anu; perhaps Ophiuchus (strength).

7g Galactic Centre; Standing gods, Sitting gods (limb joints).

7 Child or Sagittarius; Gula, Goat, Boat (chariot); Buck cocoon (bag, named ‘buck bag’ in archaeology).

6 Exile B or Capricornus; Before goat, Sitting Dog; a late Babylonian midwinter marker.

6 Exile or Capricornus; Goat’s eye, Baba’s messenger.

5c Tail or Lyra; Behind the goat, two stars (double-headed), Ninsar and Erragal.

5b Priest or Aquarius rear; Leopard (varicoloured, felid of 13 opposite). These ecliptic features are below the galactic asterisms of Cygnus Swan, and Cepheus Sea Monster.

5a Priest or Aquarius rear; Right of Leopard, Pig of Damu. This is a clue to what pig icons in all cultures, including Gobekli Tepe, may express.

4p Gal.S.Pole or Pegasus; Left of Old One, Horse (as Pegasus).

4 King or Pisces; Behind Old One, Stag; Cassiopeia at Pegasus or Andromeda star Alpheratz.

==plus an overlap of the first four as higher ‘magnitues’:

3:18 Queen or Aries; Stag breast (sacrifice), Weak stars, Rainbow (bent neck); star Hamal.

2c:18c Basket or star Algol; Stag kidney, Destroyer; Perseus Algol, formerly a red star.

2:17 Builder or Taurus Perseus; Marduk (twisted posture).

1:16 Builder or Taurus Orion; Perhaps Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions (cluster), or eclipse cycles, in the hour after the Galactic gate (or days before the Taurus-Gemini season).

“These are the 33 stars of Enlil”, ends the Assyrian list. But the list has 35, including four poles (three at the galactic pole and Bootes, indicating an Age Gemini-Taurus tradition); and some duplications, and the overlap; and some galactic decans in Scorpius; leaving about 20 characters, typical of archetypal art (average 16, plus two poles, and/or two gates, and/or two of the four transitional types).

Thus the Plough list is at least as archetypal, and mytical, and ritualist, as it is astronomical, or rather calendric. The overlap ‘clasp’ at the end expresses four of the five higher magnitudes of typology (types 1:16, 2:17, 3:18, 4:19, identified in Furter 2014; Mindprint). The other higher magnitude is part of the main list as usual (5a and 5b), where the magnitude jumps from base16 to base17 (see the list of archetypes below). Thus the ‘periodic table’ of culture is almost as complex as chemical elements with orbitals, atoms with quarks, or DNA with haemoglobin knots.

Culture parades its structure in stories and pictures, but conscious distractions are part of their camouflage. Against the elegant complexity of archetypal logic, Schaefer’s (2006) view that the Plough decans were “zodiac precursors” seems incorrect. We do not see Greek dramas as ‘soap opera precursors’, rather as more elaborate or esoteric expressions of culture, which also has dumbed-down versions. The late Assyrian version we have, of BC 687, was contemporary with the Greek zodiac, and there is probably some referencing between them. Decans are elaborate, and zodiacs are minimal versions of archetype on a stellar canvas. Both reveal the common source of cultural media, perception, nature, and the structure that underlies nature. The sky is not the only, and not the primary canvas of culture.

There is a fox in the Plough list, among three canids: type 2 as Perseus, or his legs, as a wolf over a furrow (well known among alchemical emblems); 6 Before the Goat, Sitting Dog (shuffling midwinter marker, known in Greek lore, archetypally in Capricornus); 9c Lid or Lupus as Nergal’s fox (canid). Star lore has a few more canids, notably Canis and Canis Minor of 15 Maker or Gemini, but each is distinctive, and differentiated by their other typological features. If this Lupus fox harked back to Babylonia or Sumer, that would not imply that oral traditions sustained culture. Foxes play the same roles worldwide, but that does not imply that culture merely dramatises animal behaviour. Average global frequencies of recurrent features clearly indicate a subconscious repertoire. When bards tell one another ‘their’ myth cycles, they do not attach frequencies to each recurrent feature, such as twisted posture, bovid, arms up, staff, felid, womb, canid, kind of canid, and so on. There is also a layered frequency code in culture, as there is in language. Speakers and writers use certain words twice as often, and half as often, as certain other words (Zipf 1935). Thus archaeo astronomy needs an interdisciplinary approach, including the philosophy, psychology and iconography of archetype, to study the cultural record.

ARCHETYPE ENABLES CLUSTERS OF MEANING

Cultural media use several kinds of symbolism, such as syllogism, synedoche, allegory, but they do so interchangeably, just as our dreams do, and as the Jee Jing (I Ching, Book of Changes) does. Ploughs, sowing, reaping, foxes, snakes, dragons, teeth and soldiers play out dramas that only our collective subconscious, within our natural environmental niche, could sustain. One of the astronomical versions of part of cultural repertoire, is a small canid on the polar ‘plough’, as in the Greek-Egyptian Dendera round zodiac. One mythic version is Samson’s foxes with torches tied to their tails, set loose in an enemy’s corn field. An Akkadian Agade cylinder seal shows two gods ploughing with a lion and a dragon, perhaps type 15 Maker or Gemini, ‘controlling’ the pole or plough by a ‘plough rope’ via Ursa and Draco. The hand of one god is a scorpion, indicating a celestial meridian between Gemini or the gate, and Scorpius or the galactic centre gate. There is also a tooth, bird, eight-pointed star (one of the three poles, often mistaken as a planet), crescent in a field, and three furrows (equators). The dragon extends from star, to field, to plough, its teeth ploughed in, as in an Egyptian hieroglyphic pun for goddess Sopdet (probably Venus and not Sirius, as Rabinowitz argued on Adacemia), sinking and rising yearly; perhaps as in the Greek myth of Cadmus.

Myth, art, calendar, ritual and asterisms together reveal the core content of culture. It is not all about certain codes or messages from ancestors. The list of known features of recurrent characters in art and architecture, and their average frequencies, is growing (after Furter 2014, 2016, expanded in June 2017, see an update on www.stoneprint.wordpress.com).

Table 6. Archetypes by number, label and analogous constellation (not ‘sign’); some known recurrent features with their global average frequencies:

[UPDATE 2019; The list of known recurrent features and averages was expanded by adding data from ancient miniature artworks, including Babylonian, Indian and Greek seals. See Stoneprint Journal 5 2018, and some 2019 posts].

1 /2 Builder or Taurus; twisted 48%, tower 22%, bovid 19%, cluster 14%.

2c Basket; secret 17%, container 13%, woven texture 13%.

3 Queen or Aries; long or bent neck 37%, dragon or griffin 14%, sacrifice 13%, school 11%, knife.

4 King or Pisces; squatting 25%, rectangular 20%, twins 11%, king 9%, bird 6%, field 6%, furnace.

4p Gal.S.Pole; limb joint 50%, juncture, spout 13%.

5a/5b Priest or Aquarius; assembly 30%, varicoloured 30%, hyperactive 30%, horizontal 30%, priest 15%, water 15%, tailcoat head, heart (of 12), camouflage.

6 Exile or Capricornus; egress /ingress 48%, sacrifice 13%, small 13%, U-shaped 11%, amphibian, double-headed.

7 Child or Sagittarius; unfolding 17%, bag 13%, rope 12%, juvenile 10%, chariot 8%.

7g Gal.Centre: water 15%, gate.

8/9 Healer or Scorpius; pillar 50%, bent forward 30%, healer 11%, strength 9%.

9c Lid; revelation 15%, with snake or canid.

10 Teacher or Libra; arms V/W-posture 50%, staff 17%, guard 15%, canid, hunt master, ecology.

11 Womb or Virgo; womb /interior 87%, mother 60%.

11p Gal.Pole: limb joint 68%, juncture.

12/13 Heart or Leo; heart /interior 85%, felid 20%, death 33%, war 17%.

14 Mixer or Cancer; ingress /egress 50%, bird 10%.

15 Maker or Gemini; rope 30%, ordering 25%, bag 10%, face 10%, doubled 10%, canid 8%, creation, churn, sceptre, mace, rampant.

15g Galactic Gate; gate 20%, river 6%.

Certain limb joints near the centre of artworks play ‘polar’ roles:

Axial centre or ‘ecliptic pole’; single point 100%, limb joint 26%.

Midsummer or celestial pole; limb joint 50%.

Midwinter or celestial south pole; limb joint 37%.

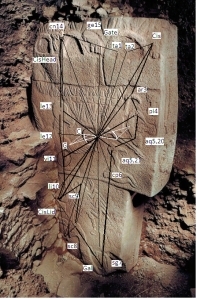

ARCHETYPES ON PILLAR D43

The design on Gobekli pillar D43 subconsciously expresses the usual five layers of archetype, including the 16 characters, several of their optional features, their sequence, the ocular axial grid, the polar structure, and the time-frame orientation.

Table 7. Type labels; Characters on Gobekli pillar D43 (noting archetypal features):

1 Builder or Taurus Orion; Reed hut (see Inana huts of twisted reeds, with animals and totems). Some Gobekli stone figurines have loophole bodies, like Chinese ‘house’ weights for leather covers, and Babylonian ‘hut’ trade weights.

2 Builder or Taurus Pleiades; Same hut or keep.

2c Basket or Perseus star Algol; Spider (weave) or freshwater crayfish juvenile (Gheorghiu 2015).

3 Queen or Aries; Flamingo or crane (long neck).

4 King or Pisces; Water-bird or ibis (bird), squat body (squatting).

4p Gal.S.Pole; Bird neck bend (limb-joint).

5a Priest or Aquarius; Water-bird heart (heart of 12 opposite), or tail (tailcoat head).

5b Priest or Aquarius; Bird sitting (horizontal), near the axial centre (ingress, more usual at 6).

6 Exile or Capricornus; Bird with triangular body or tailcoat (more usual at 5).

7 Child or Sagittarius; Skin (bag), head blank. Perhaps a seal skin bird meat fermentation cache. Often a transforming cocoon or ‘buck bag’ in rock art.

7g Gal.Centre; Large bird’s neck (limb joint), perhaps on water.

8 Healer or Scorpius tail; Large bird, forward (bent).

9 Healer or Scorpius head; Scorpion (rare in art, but expressed in Western and Mexican calendars), or freshwater crayfish (tail bent forward, moves backward).

9c Basket Lid or Lupus; Wolf (canid).

10 Teacher or Libra; Snake (guard? More typical at 9c).

11 Womb or Virgo; Womb (womb) of vulture, maternal (mother, as of the Egyptian vulture Mut).

11p Gal.Pole; Vulture elbow (limb joint).

12 Heart or Leo rear; Pendant (heart, opposite heart-shaped body at 5a).

13 Heart or Leo front; Vulture or eagle, militant (war).

14 Mixer or Cancer; Small bird (bird), far from the centre (egress).

15 Maker or Gemini; Fox (canid), burrowing (rampant inverted). Some authors identify it as a felid based on the long tail, probably an error. Some authors identify it as a left-facing ibex, certainly an error.

15g; Gal.Gate; Gap (gate) between two houses.

Midsummer; Orb. Confirmed by the vertical plane. This marker places summer on the axis of Leo1, implying spring and the time-frame in Age Taurus1, as in some other Younger Dryas artworks and buildings. However the time-frame is probably before work, as usual, expressing the era of the perceived formation of the culture.

Iconographic dating in artworks is approximate. Cosmology and myths are aids to interpretation, but art is not astronomy, nor just illustrations of myth, or ‘culturally conditioned’ trance visions, as some rock art researchers believe. Art is a fully independent cultural medium. Visual and spatial expressions operate at several levels of scale in all cultures. Pillar D43 itself expresses type 4 King in house D; while house D expresses one of the two type 15 Maker houses in Gobekli village. Similar scale levels on sites in Egypt, India, Africa, Europe and Mexico have the same level of complexity, thus culture, and human behaviour, is a given quanta, independent of the level of economic and technological maturity of the society.

SUBCONSCIOUS BEHAVIOUR IS HARD FOR THE EGO TO ACKNOWLEDGE

Artists do not await or consult astronomers, astrologers, philosophers, or dreams. And artists did not, and still do not learn, teach, record or follow a programme or code down to minute detail of archetypal features. It is all innate in our eye, hand, mind, and environmental co-ordination. And it is compulsively complete. Art and culture is all or nothing. We could not tell, design or build a different ‘story’, or half a story. We did not invent culture, and we could not change it. Thus the cultural record offers access to objective meaning, but it comes with uncomfortable implications for our ego.

Structuralist art analysis now enables conscious access to culture, and to subconscious behaviour. Human culture outlives ‘different’ cultures, its core content and styling options intact, immune against tampering. Sweatman and Tsikritsis propose that “The implications of coherent catastrophism (Younger Dryas meteorite impact) are profound, for how we interpret evidence of past events (archaeology, geology, anthropology, climatology, etc).” They estimate that the implications of a Gobekli zodiac, or systematic astronomy, would be “staggering”. But all cultures have zodiacs, decans, calendars, astronomy, and occasional artistic geniuses. The implications of archetype in the cultural record are greater than the mere presence of the usual media. And archetype raises larger questions: what are perception, meaning, behaviour, culture, and nature?

Gobekli Tepe offers a precious halfway point between Ice Age cave art, and Sumerian civic multi-media records. It deserves meticulous multi-cultural study. A brief remark in an article on Graham Hancock’s website, labels the archetypal approach as ‘lazy’, compared to the presumably hard work of correspondence ‘theory’. However correspondence theories turn out to be idle speculation on where recurrent motifes may have ‘originated’, usually ending in favour of the earliest known cultures and sites. Thus Gobekli is now considered evidence of a ‘mysterious ancient super civilisation’, to borrow Hancock’s term.

The net result of diffusionist games of ‘broken telephone’ or imperfect imitations, and successive ‘Russian boxes’ in the search for cultural inventors, adds up to already known routes of trade, acculturations and aspirations. Diffusion may involve some research, but it reveals nothing of culture or behaviour itself. Considering the theoretical context of archetype, already developed in philosophy, reflexology, psychology, anthropology, sociology, and cultural crafts (Furter 2016); structuralist anthropology is not ‘lazy’. Instead, the subconscious functions of cultural media strain our common sense assumptions.

Popular anthropology could not be blamed for its theoretical deficiencies, while some of its scientists remain stuck in the eternal catch-22s of the conscious, logical, causal, diffusionist, developmental and ‘evolutionary’ paradigm of culture. There is something much more natural in culture. Human nature is camouflaged behind common sense logic.

SOURCES AND REFERENCES

Allen, RH. 1899 Star names and their meanings. Lost Library, Glastonbury

Asher, D.J. and Clube, S.V.M. 1998. Towards a dynamical history of proto-Encke. Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy, Vol. 69, issue 1, 149-170

Banning, EB. 2011. So Fair a House; Gobekli Tepe and the identification of temples in the PPN Near East. Current Anthropology, Vol 52 n5, Oct, p619-660. Univ of Chicago Press

Bauval, R. 2006 Egypt code. Century

Burley, PD. 2013. Gobekli Tepe, Temples Communicating Ancient Cosmic Geography. www.grahamhancock, March. Also in Hancock 2015 [DISPUTED ABOVE]

Collins, A. 2014. Gobekli Tepe, genesis of the gods. Bear & Co, USA

De Santillana G, Von Deschend H. 1969. Hamlet’s Mill: An essay on myth and the frame of time. Boston: Gambit

Dodwell, GF. 2010. Obliquity of the ecliptic; Ancient, mediaeval, and modern observations; posthumously in Setterfield, http://www.setterfield.org/Dodwell_manuscript_1.html

Firestone R.B. et al. 2007. Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12 900 years ago that contributed to the mega-faunal extinctions and the Younger-Dryas cooling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Vol. 104, issue 41, 16016-16021

Furter, E. 2014. Mindprint, the subconscious art code. Lulu.com, USA

Furter, E. 2015. Art is magic. Expression 10, Dec. Atelier Etno, Italy

Furter, E. 2015. Mindprint in mushroom /psiclocybin, peyote /mescalin, sugar, and chocolate art. On www.mindprintart.wordpress.com

Furter, E. 2015. Rock art expresses cultural structure. Expression 9. Atelier Etno, Italy. Also in: Rock art Where, When, to Whom. Ed. E Anati 2016

Furter, E. 2015. Structuralist rock art analysis. Association of Southern African Professional Archaeologists (ASAPA), Harare. Univ of Zimbabwe, in press for 2017

Furter, E. 2015. Art and Rock art express the structure of culture. www.grahamhancock.com Author of the Month, September

Furter, E. 2016. Colonial artists re-style the same characters. Expression 14. Atelier Etno, Italy

Furter, E. 2016. Stoneprint, the human code in art, buildings and cities. Four Equators Media, Johannesburg, South Africa. Extracts on www.stoneprint.wordpress.com

Furter, E. 2017. Pregnant is the most consistent typological gender. Expression 15, March. Atelier Etno, Italy

Furter, E. 2021. Hercules, Arcadia, and Greece myth maps. Stoneprint Journal 7. Four Equators Media, Johannesburg ($18 plus postage, ideally order chosen editions with the book Stoneprint (2016), via edmondfurter at gmail dot com)

George, L. 2013. Painting postures: Body symbolism in San rock art of the North Eastern Cape, South Africa. M thesis, Univ. Witwatersrand, wiredwits

Gheorghiu, D. 2015. A River Runs Through It:: the Semiotics of Göbekli Tepe’s Map (an Exercise of Archaeological Imagination). Aug. Researchgate. IN: Rivers in Prehistory; A Vianello, Archaeopress, Oxford

Gigal, A. 2016. Megalithomania lecture on Giza island; http://beforeitsnews.com/alternative/2016/05/megalithomania-antoine-gigal-the-divine-island-of-giza-3355165.html

Gombrich, EH. 1979. 1984 Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art. Cornell Univ. Press

Hancock, G. 2015. Magicians of the gods. Coronet

Herschel, W. 2015. Hidden Records, website [DISPUTED ABOVE]

Hunger and Pingree. 1999. Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia

Jung, CG. 1934, 1954. Archetypes of the collective unconscious. CW

Jung, CG. 1964. Man and his symbols. Dell

Laue, G. 2015 Gender statistics in South African rock art; preliminary report. ASAPA biennial conference, Harare. University of Zimbabwe, in press 2017

Leach, E. 1970. Claude Levi-Strauss. University of Chicago Press

Neugebauer, Otto; and R Parker. 1969 Egyptian astronomical texts 3; Decans, planets, constellations and zodiacs. Brown Univ

Popper, Karl. 1963. Conjectures and Refutations. London. Routledge

Rappengluck, M.A. 2004. A paleolithic planetarium underground, the cave of Lascaux Part 2. Migration and Diffusion Vol. 5, iss 19

Rohl, D. 2007 Lords of Avaris. Century

Schaefer, Brad. 2006. Origin of the Greek constellations. Scientific American, Nov

Schmidt, K. 2003. The 2003 campaign at Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey’. Neo-lithics Vol. 2, 3

Stephany, T. 2009. Myths, mysteries and wonders. http://www.timothystephany.com/gobekli.html [DISPUTED ABOVE]

Sweatman, M, and Tsikritsis, D. 2017. Decoding Gobekli Tepe with archaeoastronomy: What does the fox say? Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 17, no. 1 [DISPUTED ABOVE]

Temple, R. 2003 Netherworld. Random House

Von Petzinger, G. 2016. First signs: Unlocking the mysteries of the world’s oldest symbols, Atria

White, Gavin. 2013. Babylonian star lore, an illustrated guide. Website; https://solariapublications.com/2011/10/25/mul-apin/

Wylie, Alison. 1989. Archaeological cables and tacking: the implications of practice for Bernstein’s options, beyond objectivism and relativism. Phil of Social Sciences 19, n1, March

Zipf, GK. 1935. Psychobiology of Language. Houghton-Mifflin

Zipf, GK. 1949. Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort. Addison-Wesley

The shape of Gobekli Tepe is a clock face, dial plate… it means the time for human beings.

LikeLike

Muzaffer, we express the same five layers of archetypal features and spatial elements in all built sites, including the few sites now known to have preceded Gobekli. One of the five layers is in the relative position of certain markers in the central area, to the character types in the periphery of an artwork or a built site. This layer acts as a kind of clock face. It was present in cave art of nomads who lived in portable camps, about BC 26 000. It remains present in works of artists, architects, and the collective work of communities today. There were people, homo sapiens, long before Gobekli. It is special since it is the oldest remaining monumental, perhaps socio-political or memorial site. It could mean the time of alliance, treaties, annual feasts and hierarchy. All of these indicate a phase in technology and civilisation, for which we have had the capacity since we became human. Our maturity phases are triggered by population density. As the late archaeologist Schmidt said, it is not a kind of Eden. For more context you could see my book Stoneprint (2016). And Andrew Collins’ book on Gobekli. Greetings, Edmond

LikeLike

If you meant that Gobekli Tepe was ‘Eden’, no, we were human many milennia earlier, before the Ice Age. Schmidt also warned people not to see Gobekli as some kind of ‘Paradise’ or ‘Creation’. Some archaeologists have noted that Gobekli was not the first kiva-styled pillared re-built site in the region. The weather after the Younger Dryas certainly improved, but it was a time for all life, and for population explosions of all species.

LikeLike